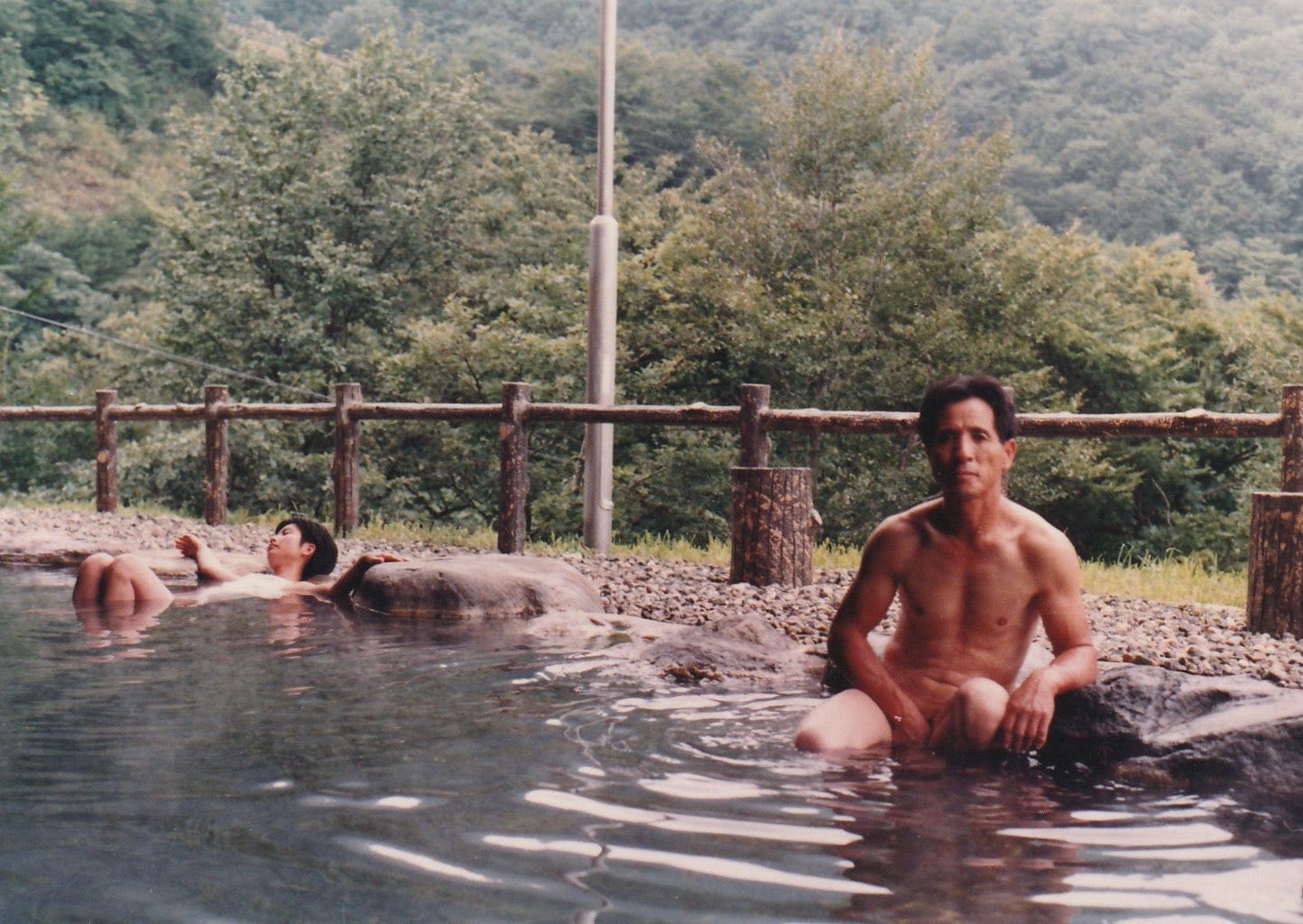

My Jiichan has been ancestor for almost one full rotation of the sun and I hear his voice teaching me about Jizo Bodhisattva, guardian deity of children, travelers, and the unborn. My vocation always creeps up on me from past future tense, traces foreshadowing my current path as a birthkeeper, one who guards that passageway between the worlds. Jiichan’s voice found me again, while looking through footage from the last time I was in the motherlands. I landed there in the wake of supporting a postpartum sister after a stillbirth of twins, creative producing her sitting-in with that mourning through helping her make a film following the dark mystery of that loss, spiraling inward toward lineage, land, finding within herself an unbroken umbilical cord of belonging. I traveled with her family to ancestral lands and at the end of it all, an opening appeared for me to travel to my homelands with my grandparents. I believe this was the last time my grandfather visited his birth place before he passed into spirit.

I carried a camera with me at that time, and I look back now and observe what drew my attention six years ago, before I moved through a series of ruptures that opened up the sky and revealed the aperture through which light streams in, weaving this world into form. My camera often pointed in the direction of child tombstones, and in one of the clips, the one I hear narrating at my side is my Ojiichan, explaining the enlightened being who ferries the spirits of children who have died across the great river to return to the peace that is their essential nature. Those are my words, not his. His words, translated, were: “You see all of these children here? The Jizo Bodhisattva of children helps the spirits of those who have died to find their happiness.”

I don’t know about that word happiness, and I wonder how he related to it, that man who was always smiling but deeply discontented, dissatisfied, in deep quarrel within his soul until his very last conscious moment. I saw it with my own eyes - spirit brought me down to southern California at that time. I came down to weave a quilt in which to carry my drum to the mountains where my people come from, but that’s a story for another day. My grandpa entered his death portal, and I was there by his side. In the mornings I’d bike to the ocean to catch my breath, and I watched the dolphins every single day in the dawning light, weaving between air and water, above and below, opening up the interstices for my Jiichan to slip through, out of this world and into another. Since the day he passed, I’ve never seen another dolphin at that beach.

My Ojiichan was a scorpionic neurodivergent man of god who lived in the realm of spirit and intellect, sought self-importance to fill the void of his wordless mother’s love, caused harm to his own children by his own neglect and aspirations to grandeur, spoke easefully and gently with animals and plants but resented that his fate was to work with land which he imagined himself above, indoctrinated with japanese nationalism while also holding curiosity and longing for his indigeneity. I say all of this to interrupt any tendency toward romanticizing elders and ancestors, especially those shaped by patriarchal imperialist overcultures, while receiving with gratitude the knowledge and love they transmit, holding them as complex expressions of culture, history, and spirit.

I miss him and his memory haunts me. His life, to me, is a cautionary tale warning of the consequences of spiritual bypassing, at every level of one’s life. I wrote about him once, years ago:

Split, ripped and bursting, out of farm husband’s sleeping mouth come spilling dried silver fish, California gold that never undreamt itself, worn leather volumes on shintoism and a religion no one has ever heard of— the one he has tasked himself with proselytizing and has failed. Dabbing drool from the corners of his cracked lips, farm woman finds that, for the second time this decade, farm husband has knocked all his teeth out. Fallen again from a high place, climbing magnolia trees to saw down the rotting branches, and believing himself to be young.

Believing himself to be young, farm husband’s books still speak to him in spools of dreams, of the greatness lying before him like a vast unmined ocean, brimming with sea strands of spectacular sea beings. Approaching the eroding edge of his body’s second century, he sees himself at the beginning of his life, a prophet awaiting prophecy.

A prophet awaiting prophecy, he will not until his last breath see the words written in clouds like a banner across the sky: my life was a river that missed its course. Bowing before the altar and the fresh offering of cut persimmons, he finds that the old ceremony songs and the church songs of this country weave together like a deer weaves between the forest and the road. I once, was lost, but now … He recognizes the song in two languages but can sing neither. Blinded by a nationalism fed to him through the wound in his manhood, he cannot see that neither nation loves nor protects him.

Sometimes it feels like I have inherited his karma - the opportunity to walk close to spirit within the teachings and traditions of our lineages, and the responsibility to engage those traditions in a way that opens us into the fullness of reality as it is. A reminder that walking a path of intimacy with spirit will never come at the expense of presence with what is unfolding right before us or within us, requesting or begging for our attention.

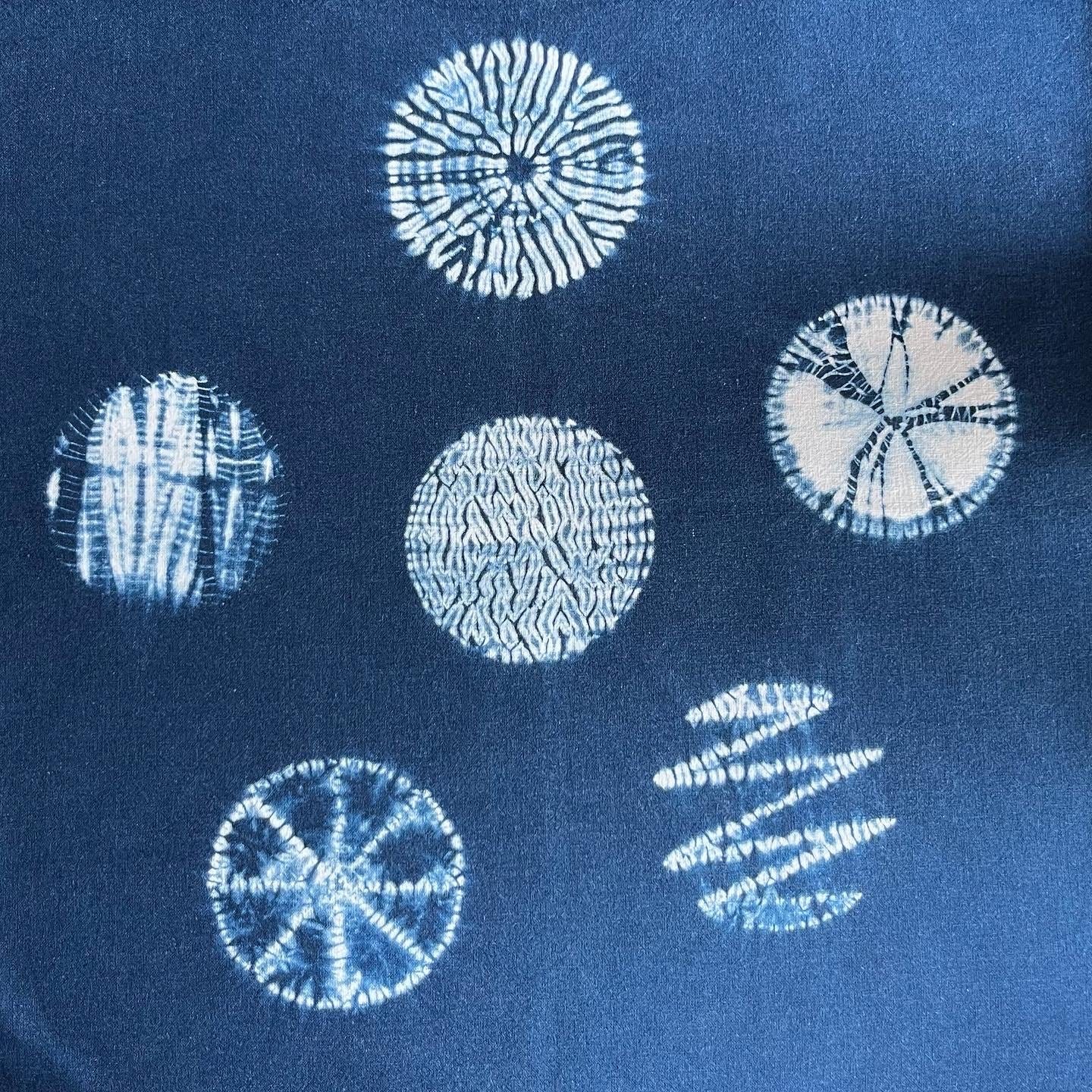

I had a conversation a few weeks ago with a former Buddhist monk and writer, Matthew Gindin, about invoking Jizo Bodhisattva in the context of the ongoing genocide of Palestinian people. In January 2024, I collaborated with clay studio Artillery Gallery, political collective Nikkei Resisters, and artist Champoy, to create a fundraiser and ritual mourning space, Mizuko Kuyo for Child Martyrs of Palestine. Mizuko Kuyo is a Japanese Buddhist/Shinto ritual that translates literally to “water child accompaniment service” and calls upon Jizo Bodhisattva to caretake the spirits of deceased and unborn children into the realms that follow this human life. I shared about how we created statues of Jizo Bodhisattva with clay, praying with our hands and earth, circling around the fire to imbue the clay with spirit and calling on Jizo-san to take care of those child spirits who had been denied the right to life, the right to a dignified death, and the right to traditional rites and ceremonies that support loving transition into the afterlife. Funds from registration were directed toward Gaza Mutual Aid Solidarity, a collective of Palestinians in diaspora gathering and distributing funds to community members on the ground in Gaza who are providing meals and life-saving infrastructure to those surviving this brutality. They are still welcoming monetary contributions to their work.

Michael asked me a question I found relieving to receive. He said, “So I’m hearing that you all were calling on Jizo to literally take care of these child martyr’s spirits. But what about within yourselves? What did this ritual call upon within you?” What I shared with him was that engaging in these ancestral rituals is our insistence upon remaining awake (conscious), feeling (living), emotionally, spiritually, and politically engaged as the months roll on, as life and death through each new season, as the death tolls rise, and old estimates are replaced with numbers in the hundreds of thousands, as we are pressured to normalize the genocides and ecocides we witness, to integrate them into individualist capitalist productive lives. Holding these rituals is by no means a replacement for organizing and direct action, but it does ensure that we do not lose our own spiritual and political aliveness amidst systems that prefer us numb, dissociated, and resigned.

Transformative grief activist, movement strategist, and writer Malkia Devich Cyril said it best on Prentis Hemphill’s podcast, Becoming the People (I highly recommend listening to this whole episode):

Devich Cyril talks about how we must be “radicalized by loss, and transformed by grief.” We know that radical means relating to the root, and the roadmap we are offered is that attending our grief is to “reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside [ourselves] and touch that terror and loathing…that lives [there]” (Audre Lorde, The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House).

Devich Cyril uses the word accompaniment throughout their interview to describe the communal practice of attending our individual and collective grief, which is the same word included in the kanji characters that spell Mizuko Kuyo, 水子供養 - water, child, accompaniment, nourishment. Who and what can we call on to accompany us in our grief, in our reckoning with the unbearable within and around us?

Michael Gindin, the former monk, told me about an essay he wrote about relating with bodhisattvas as archetypical energies we each hold, and less as external forces to whom we make petitions. He writes, “Throughout Buddhist stories, [bodhisattvas] have been mythologized, prayed to, depicted in Buddhist art, worshipped, channeled, and even identified with. Some Buddhists think they are real, and others view them as products of the mind—focuses of meditation or imagined embodiments of archetypal forces. Still others refuse to make a clear distinction between them being real and being unreal, as in the case of one Tibetan teacher who, when asked if cosmic bodhisattvas are real, replied, ‘Yes, but they know they are not.’” Michael goes on to share his own understanding of bodhisattvas: “They become a way to access the wisdom we hide from ourselves—the wisdom that is unconscious.”

Hearing this perspective has stimulated something in me, and reminds me of the teachings of another relative of mine. I remember sitting in ceremony with her, holding cedar in my hands, making a prayer for my life. I’d seen something within myself that horrified me, my own embodiment of the energetics of colonialism in close relationships with loved ones, insidious ways that extractive culture had seeped into and caused harm within friendships I cherished the most. Disgusted by what I’d seen within myself and wanting to rid myself of it, I made a prayer to eradicate every trace of white supremacy from my psyche, offered the cedar to the fire and brought the smoke over my body, hoping it would cleanse me of this poison. My relative, watching and listening, told me, the cedar isn’t a magic wand; it’s not going to magically rid you of anything. I remember feeling embarrassed, to have exposed myself in the fantastical thinking that it would be so simple, as effortless as asking something outside of myself to transform me. I asked her, so what do I do? And she told me that we do not approach our programming like something to get rid of. It has, after all, hooked itself into our deepest core wounds; that’s how it works. So we must approach it as we would approach any other trauma. We must be willing to sit with the pain to understand it, and over time, apply the antidotes of wisdom and compassion.

The truest and most effective medicine is that which we cultivate within us. I think of the influence of growing up in a consumerist society, that conditions us to believe there is always something we can buy or steal or externally act upon in order to alleviate a painful or uncomfortable feeling. We become removed from the actual and natural processes of change. There is a diminished tolerance for sitting in the discomfort long and patiently enough to listen for how it got there in the first place, and what may be needed in order for it to begin to move or transform, not by force, but because a need has been met, a hunger has been nourished, on a root level. Change is a process that emerges through agitation like the formation of a pearl, the irritation of salt and sand stimulating an ongoing process of refinement, giving rise to a luminous consciousness.

I think of the times I have called on Kannon-Sama, or Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion. These have been some of the most desperate moments on my journey, when out of nowhere an inkling has arisen to call upon that holy embodiment of compassion, to invoke her into my own body, my own consciousness, to feed myself with her medicine, to protect myself from the fires of self-hatred and self-cruelty, to shield myself with her divine love. And her love has never not been mine. And her name has never not lived within me.

Who do we need to become in order to embody the prayers we speak? In what ways is prayer a devotional practice of inner alchemy? Of bringing into alignment what we speak, what we long for, and how we act? A teacher of mine, Rachelle Garcia Seliga, offered this as a definition of integrity: when what we say, what we feel, and what we do, are all the same. When people criticize “thoughts and prayers” as all some can muster in response to the suffering of others, it’s not prayer in its truest essence we are criticizing. That is prayer only in name, and in reality is a bypassing of reality, a refusal to engage our full humanity in relationship to the suffering we witness as, conveniently, apart from us. Joy Harjo in her “Eagle Poem” writes,

To pray, you open your whole self

To sky, to earth, to sun, to moon

To one whole voice that is you.

To pray is to refute separation.

I think about my Jiji, a man who thought himself on a spiritual path, wrestling with his demons until the literal day that he died, the musculature of his resistance to the reality of this life stronger than three of us with our youth still in us combined, his entire body refusing rest. His last seven days on this earth were spent gripping to life, begging for death, haunted by internal monstrosities, his consciousness suspended somewhere in the in-between. My Obaachan tells me that he is in heaven now, and everything I know about our journey after we leave these bodies tells me it’s not true. Heaven is not a place we simply arrive; it is a consciousness we cultivate over lifetimes. Of course, I won’t tell my grandmother otherwise. Sometimes to love is to shake awake, and sometimes to love is to allow what comforts.

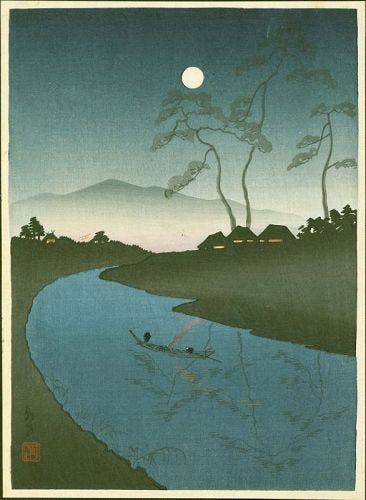

天の川 - River of Heaven - Amanogawa -Sacred Milky Way - to you I admit: the rites are not intact - we did not pray for him on the 49th day - those rites are a language of love and service - the destiny of an ancestor is in part determined by how those still living choose to honor their memory - we are your karma incarnate - what mark have you left on us? What responsibility have you nurtured in us? I do not know the rites but I have these words and I have this heart - I pray for my Jiichan’s spirit as it has imprinted within me - I tend to those wounds of an unloved child of a wounded and absent mother - I know that pain - it has entered my body - may it be mine to transmute - mine the living - mine the able - may my dedication be one of the laboring oars of the boat that ferries him to his next shore ~

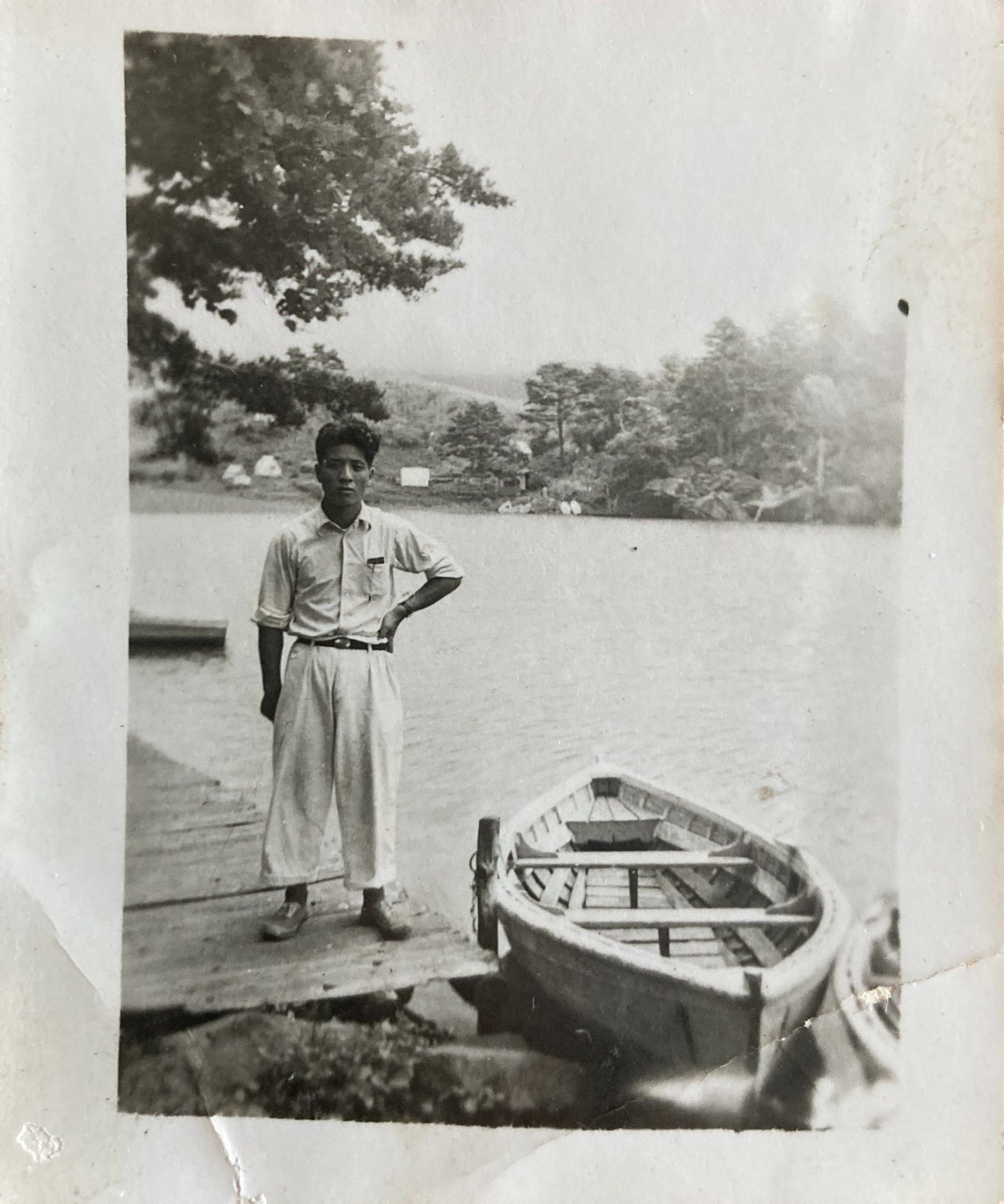

In the picture, he stands beside the boat at the river that birthed him, contemplating his departure. Suspended in the in-between, but not forever. Whether by choice or by nature, we will all leave our bodies on the shore and surrender to the ferrying of our spirits into the next worlds to continue on our journeys of evolution.

And the river doesn’t stop - it never has, and it never will -

What are we to do with our ancestors’ unfinished mourning?

She begins to feel fear falling off of her shoulders like a slippery shawl. The comfort she has grasped so tightly, thinking, always thinking about how to escape the pain, how to fix it, how to rid herself of it—something about this music makes her feel that, even just for a moment, she can let it fall down and rest around her ankles. Not alter anything about it, except for its hold on her and her hold on it. Some of what she feels is sharp and spiny; some of it is sweeping and majestic. Not one bit of it does she resist, observing how resistance worsens the discomfort, and she begins to sway in her body, a moving vessel, carrying an entire cosmos of vital feeling.